Aliens, Animals, and the Emergence of the Giant Vampire Squid

[This version combines elements of three related lectures — “The Alien and the Octopus,” a talk given at New Directions in Science Fiction Criticism series at Indiana University, January 2016; “The Alien and the Anima Mundi” given at University of Alabama in Huntsville Honors College, September 2015; and “Aliens and Animals,” a talk given for University Courses and Society for the Humanities, Cornell University, September 2014.]

It may seem odd at first to choose to work in science-fiction studies and animal studies at the same time – but it is actually quite a natural combination. After working in technoculture and sf studies for more than thirty years, I couldn’t help but notice that animals — and carbon-based non-human beings in general — were being steadily deleted from futuristic visions. The posthumanity envisioned by more and more writers seemed to entail being post-animal – maybe even primarily post-animal. Critical animal theorists were noticing that this coincided with the disappearance of animals in daily life in the hyper-technologized western world, along with dramatic species extinctions and the ravaging of biodiversity everywhere. The destruction of natural habitats for resource extraction and human settlements, the effects of war and human induced climate change have impacted animal life not only in the Eurosphere, but in those places where animals are still revered—as in India, perhaps the most animal-friendly civilization in the world. Not all animals are being wiped out, of course; the ones that are useful to human beings – which now means basically as food – have been enmeshed in the system of high-tech industrial breeding and slaughter, concealed from public view. The reduction of our encounters with animals basically to household pets, backyard critters, and “trash animals” reflects the intense urbanization of the human zone and the replacement of animal labor by machinery.

This exile of animals means the removal of a world of beings who basically co-constructed our evolution with us, including our social evolution. Non-humans have been excluded precisely because human cultures want to assert their distinctiveness from the mutable, fleshy, infectious natural world, and to demonstrate their suitability for transcendence into higher realms. This animal exile has enormous implications not only for the actual animals, but for the intricate web of symbols and analogies that we base on them – including our discourses of sexuality, passion, instinct, intelligence, and the politics of nature.

But the connection between technoculture studies and animal studies is not an exclusively critical one. Both animal studies and sf studies share a core concern with the Other: SF’s aliens and animal studies’ other-minded creatures are in many ways similar. Both aliens and animals are beings to whom human beings can compare themselves. Without them, we would remain alone. Materialist-scientific cultures can no longer take comfort in a universe populated with many kinds of minded beings. In non-modern worlds the human being can define itself against fairies, gods, daemons, angels, a whole pantheon of nature spirits, and especially animal spirits. But once the supernatural has been wiped away, human beings seem to stand alone, an evolutionary singularity – without any comparable beings that might help us to define ourselves. If, in classical humanist terms, the human is defined by its capacities for self-reflection and awareness of its own mortality, which we alone among earthly species allegedly possess, we have nothing to measure ourselves with, to allow us to see our limits, or our connections. If there is no alternative form of this consciousness and capacity, how can we know that what we consider knowledge – including self-knowledge – isn’t just the organized hallucination of our powerful neuro-wiring? To keep this solitude from overwhelming us, we look for beings that can act as parallel singularities. The humanist qualities that once marked the glorious superiority of homo sapiens to the rest of the world — abstract intelligence, language, reason, technology, political organization – become black holes if they don’t mean anything beyond our own self-oriented species worlds. Hierarchical superiority inevitably leads to isolation. So we begin to look for those qualities in the other living beings around us, and project them in beings from other worlds that we imagine we may yet meet. The alien is the fictive event horizon of a parallel singularity from which we may derive what we are. To write a good alien in sf one must create the conditions for its alternative material evolution – in sf this is called “world building.” In animal studies, researchers posit the internal and external physical constraints on the perceptions and cognition of individual species, which the great German biologist Jakob von Uexküll named their “Umwelt.” The dictionary translation of the word is: “environment,” but in Uexküll’s now-accepted usage Umwelt means “self-oriented world.” In both sf and animal studies we imagine the consciousness of other beings as intermeshing self-oriented worlds. In both sf and animal studies, these worlds are imagined ones: in sf because they are invented, in biology because they must be imaginatively inferred.

Good sf aliens are the products of material evolution. The rules of the science-fictional imagination dictate that they cannot be formed by forces and rules different than physical forces of the universe and their sublimations in material culture. Aliens may evolve from different elements and base molecules, they may emerge from radically different environments. And since sf is an art of playful rationalization, not a strict conveyor of scientific knowledge, any evolutionary dynamic between environment and organism is in play as long as it is fittingly explained, on a spectrum from models based on the actually existing science to icons from the pop unconscious. Whatever their fundamental elements or their evolutionary paths, sf demands that aliens manifest some intelligence and intentionality that shows they have complex minds.

Recently, much of the philosophical interest in animals has been drawn to the question of animal minds. There are few thinkers left who dispute that animals – at least so-called “higher animals” – have some sort of complex mental activity. Now, often it is argued that animal consciousness remains on a lower level than the human because human beings have self-awareness – that is, they process information not only about their environments and their bodies, but they are aware of themselves as autonomous entities. This is what we might call the “humanist core” – that there really is such an autonomous self to be known, and that human beings have the faculty to know this about themselves as if from a position outside themselves. Clearly, this involves a bit of a paradox: if the self is perceived, what do we call the mental entity it is known by? One tack for exploring this problem of human mental superiority has been the attempt to imagine what it is like to be another kind of animal mind. In some cases, this has led to the dramatic claim that some animals like the higher apes and dolphins also have the capacity for self-recognition – they can recognize themselves in mirrors, and presumably can undergo some sort of mirror stage and might be accorded the status of personhood. In other words, they are like us at least as much as they are different.

However, the most famous such thought-experiment of imagining another mind is Thomas Nagel’s classic essay, “What is it like to be bat?” which is studied (I hope) in every introductory philosophy and psychology class. Nagel posed a problem of imagining alien minds: how can we imagine the experiential viewpoint of a being whose entire sensory apparatus, its mode of constructing a world-picture for itself, and of inhabiting it, are radically different from the human? As Nagel writes: “Even without the benefit of philosophical reflection, anyone who has spent some time in an enclosed space with an excited bat knows what it is like to encounter a fundamentally alien form of life.”

Attempts to understand a bat – i.e., to conceive what it is like for the creature to be that creature – are stymied from the start, in Nagel’s view, because we are confined by the limits of our own material subjectivity, the exact parameters of what it feels like to be human beings. We might be able to describe the bat’s behaviors and neurophysiology, but those are our categories. The bat’s “categories” remain opaque for us. A similar exploration has been done by the marine biologist Peter Godfrey-Smith in his 2013 essay “On being an octopus.” Godfrey-Smith considers the octopus a more alien creature, since it does not share the mammalian heritage of both bats and humans — and yet it displays apparent complex problem-solving behaviors and observational intelligence.

Nagel is less interested in the existential predicament of bats than of human beings, of course; it is we who are caught in the bind of knowing that we cannot truly imagine being anything other than ourselves. We are the ones who cannot know ourselves by comparison with some other form of mind that is both significantly similar and different, Nagel again:

…in contemplating the bats we are essentially in the same position that intelligent bats or Martians [Nagel’s footnote: “Any intelligent extraterrestrial beings totally different from us”] would occupy if they tried to form a conception of what it is like to be us.

Such thought-experiments imagine animal minds – or at the least the unimaginability of them, their radical difference – not necessarily to admire or revere them, but to disrupt the narcissistic self-admiration of human self- consciousness. Respect for the diversity of minds follows — or should.

This interest in the diversity of mind places both sf and animal studies smack in the middle of posthumanist thought. There are at least three strong currents of posthumanist thinking that flow through SF and animal studies. I’ll call them the deep-ecological, technovisionary, and the philosophical. The deep-ecological is the least problematic of the three. It flows from the deep-ecology of thinkers like the Norwegian philosopher Arne Naess and the Gaia hypothesis of James Lovelock and Lynn Margulis; its advocates tend to view homo sapiens as an imperial usurper of the networks of nature. Its posthumanism is literal: imagining how the world would be better if the human role were reduced radically, or if humanity went extinct altogether. Technovisionary posthumanism is probably the most widely known. It too speculates on the possibilities of a future world and transformed values, and even sometimes the extinction of the biological entity that we now call the human. Advanced digital technologies and breakthroughs in nanotechnology, genetic engineering, and artificial intelligence, so the vision says, are creating the possibilities for a more flexible and intelligent entity than the current version of humanity. A cyborg ontology will sweep away the limits imposed by our biological heritage – and some technovisionaries also imagine that the human species will be replaced by any number of cyborg forms and networks, maybe even flowing into the great insular universe of the Technological Singularity. The final form of posthumanism, the philosophical, is what those of us in the Academy are most familiar with: the great distributed project of breaking down the arbitrary hierarchies and boundaries that enforce the centrality – and hence the claimed superiority – of the western ideal of the human being: the individual, self-aware, creative sovereign over the unconscious parts of the world. The many schools of posthumanist philosophy are connected by their shared project of undermining the mystique of the Self through the recognition of the Other.

It’s not hard to see how these currents stimulate sf studies and animal studies. Sf artists have been inventing variants of the non-human or posthuman other since before the beginning. Think of Gulliver’s Houyhnhnms and Yahoos, Victor Frankenstein’s creature, Dr. Jekyll’s ape of evil Mr. Hyde, Dr. Moreau’s beast-men, the Martians of War of the Worlds, the Morlocks and Eloi of The Time Machine – and we see similar motifs in various kinds of New Human Beings, from the supermen of late 19th century Russian utopian sf to the Tokyo bohemians of the 1990s. SF can be seen as the culture’s encyclopedia of alterations of the human substrate: mutants, hybrids, cyborgs, and aliens. SF is one of the great cultural projects of imagining alternatives to historical notions of the human being. SF is primarily a fiction of thought experiment – and while its visions sometimes become blueprints, and its dreams are sometimes actualized in real life, it operates in the suspended zone of the imagination, of fiction, and thus has much in common with philosophy – which from a literary person’s perspective, is a very rigorous form of fiction. The relationship of animal studies to posthumanism is primarily ethical: the demolition of the rigid divide between human and nonhuman animals has a purpose and an end-point in a better world. For example, both animal-studies scholars and posthumanist philosophers argue that the grand enterprise of humanistic enlightenment has been predicated on the exclusion, and outright killing, of those excluded from the definition of the completely human. At different times these have included women, conquered peoples, non-Europeans, children, gays and trans-sexuals, and most certainly animals. These groups are not only not accorded the protections of universal human rights, but the treatment of their most abject becomes a blueprint for the treatment of analogous groups of abject humans when push comes to shove.

Once we grant these shared perspectives, we can see that the connections between aliens and animals are many and deep. Many – and perhaps most – of the alien creatures represented in visual and literary sf are at least partly based on animals, or have evolved from a different branch on the galaxy’s evolutionary bush than terrestrial primates. Sometimes they are not zoomorphs, but plants – like the pods in The Invasion of the Body Snatchers, or John Wyndham’s triffids. But mostly they are animals. This goes back to pre-extraterrestrial times, when Pliny collected wild travelers’ tales of dog-headed and snake-bodied people.

Jonathan Swift plays with highly evolved horses – the Houyhnhnm – to contrast with the foul humanoid Yahoos. In sf per se, we see technologically spawned giant ants, mantises, spiders, rabbits, landsnakes, spiders,

prehistoric creatures quickened to life by nuclear explosions, and alien beings with obvious animal cores. Think of the sluglike Jabba, the bizarre rabbit Jar-Jar Binks, the metamorphic hybrid xenomorphs of the Alien films, the bat-like visages of the Ferengi,

the reptilian epidermis of the Klingon, the arachnoid/reptilian/dog hybrid of the Predator’s face,

the “prawns” of District 9.

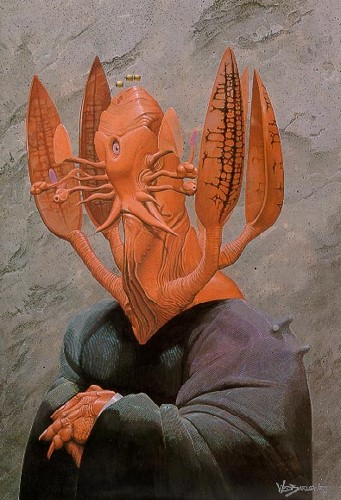

Literary sf has many hybrid variants: Medusa-sluglike Ooloi of Octavia Butler’s Xenogenesis trilogy, cybernetic flies of Stanislaw Lem’s The Invincible, intelligent flatworms of Hal Clement’s Mission of Gravity, mosquito-humans of China Mieville’s The Scar, extraterrestrial turtles of Le Guin’s Lathe of Heaven and many more. SF artists have been inspired to construct images of ever-more sophisticated alternative evolutions, leading to intelligent alien agents in radically different zooforms. Here is my favorite, by the celebrated fantastic artist, James Barlowe:

The painting, entitled “Elytracephalid,” was commissioned for the cover of Newsweek in 1993. (It was not used.) It portrays a sea-worm that has evolved into a dignified jurist of some alien bourgeois Renaissance.

While Barlowe’s association of the animal with the alien is dignified and uplifted, more often the reverse is the case: the alien’s animality tends toward the bestial – and is used as a displacement of racial, sexual, and class othering – given that all groups outside the magic circle of white, male, bourgeois overlords have been relegated to the subhuman zone. Nor is this exclusively a modern western phenomenon. It appears to be a constant in patriarchal cultures. Nowadays, this has been closely observed and articulated by what we call animal philosophy – most prominently associated with Jacques Derrida and Giorgio Agamben in Europe, and with Carol Adams, Marc Bekoff, and Donna Haraway in the US. The notion of human superiority is the product of what Agamben calls “the anthropological machine” – a ceaselessly churning intellectual industry that draws the line between the “true human” and the non- or sub-human. The true human being is, of course, the one who must be protected and nurtured. The others may be treated as exploitable, killable, and ultimately as food.

The animal qualities of the alien are often combined with other qualities of the excluded human – racial and ethnic ones. Think of the Mongol, Rastafarian and samurai fusions of the Klingons or the quasi-Jewish Ferengi of Star Trek: TNG, or gender bestialization as in The Wasp Woman.

Now, while this connection of the earthly animal and the extraterrestrial alien is as old as sf itself, it is clear that it is highly variable. Especially since sf has become a technocultural phenomenon, it has been influenced by the speed of modern meme-production machinery in a sort of accelerated evolution. Many of the most popular metamorphic monsters of our time have animal pedigrees – vampires were once bats, werewolves were once… well, you know, wolves. Zombies are an interesting exception, at least at first glance. They are not associated with a specific animal type, but they are in a way the most abject versions of animality itself in the turbo-humanist mind-set. They are flesh-eating machines. They have no recourse to reason, to superego, to compassion – they exist to eat humans. We are currently in a phase in which we see zombies humanized, as it were, that is, given agency and subject positions, as candidates for empathy – but this is mainly by allowing them to maintain some of their “humanity.” In other words, their zombie-condition is that of an animal machine, their resistant minds that of human beings. The anthropological machine at work.

This same humanization of the animal-like monster is evident in the evolution of the vampire and the werewolf, for example. While they were always somewhat human, at least in superficial respects, we’ve seen both gradually manifest more and more sympathetic “human” qualities. Both become sexy beasts, until they become superhuman, drawing on different cultural traditions, appropriately kitsched-up. They evolve from being monsters to being demigods. This may be an embedded feature of otherization – it’s clearly integral to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein.

Which brings us finally to the octopus – and cephalopods in general. We are witnessing a cultural boom in cephalopods. Tentacles are everywhere. In popular fiction and art tentacles are the new fangs, as the British scholar of Gothic fiction Roger Luckhurst recently put it. Multi-armed sea monsters have become monsters of choice in fantastic erotic fiction and animation, and more and more science-fiction and fantasy films require writhing, whipping, suckering, sliming tentaculation. In popular science, as well, cephalopods are enjoying a renaissance. The Internet features hundreds of videos displaying the mimicry, tool-use, and intelligence of octopuses, the stunning chromatophoric communications of squids, and the charmed relations of the Chambered Nautilus and the Golden Ratio. In scientific culture, cephalopods have transitioned from being quintessentially non-anthropomorphic animals to the newest, most distant sharers of problem-solving consciousness.

Luckhurst considers the tentacle the contemporary emblem of genuine otherness – the mark of creatures that live in the deep trenches between myth and science. But in the first half of the 19th century cephalopods were even more clearly charismatic embodiments of otherness. Readers of Melville’s Moby Dick may recall the chapter entitled “The Squid.” In it, the crew of the Pequod encounters a giant sea beast that they first believe is the white whale. When they row out to it, they discover it is not a whale, but a much larger creature floating just below the surface, a squid so large and fluid that it seems dimensionless.

A vast pulpy mass, furlongs in length and breadth, of a glancing cream- color, lay floating on the water, innumerable long arms radiating from its centre, and curling and twisting like a nest of anacondas, as if blindly to catch at any hapless object within reach. No perceptible face or front did it have; no conceivable token of either sensation or instinct; but undulated there on the billows, an unearthly, formless, chance-like apparition of life.

Melville did not know much about giant squids – he never saw one – so Ishmael’s description is much less concrete than his famous descriptions of cetaceans. And this lack of concreteness is also a philosophical point. Ishmael sees the squid as a violation the rules of form – it so alien to him he has difficulty perceiving it. In contrast with his meditations on the difficulty of seeing the face of a colossal whale, with the squid he has come upon a creature that he believes literally has no face, and hence no interface with the human mind.

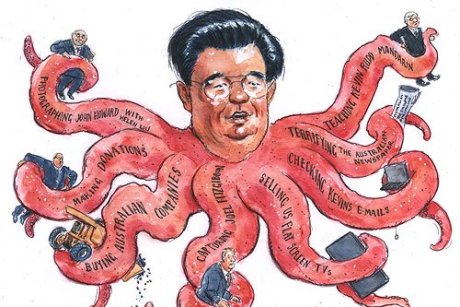

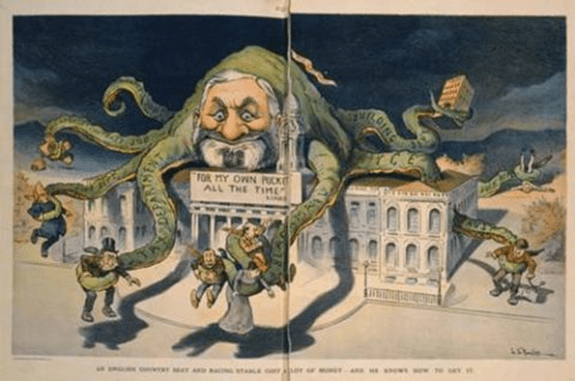

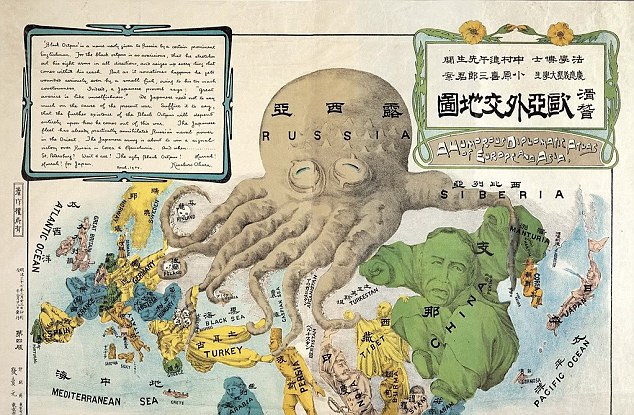

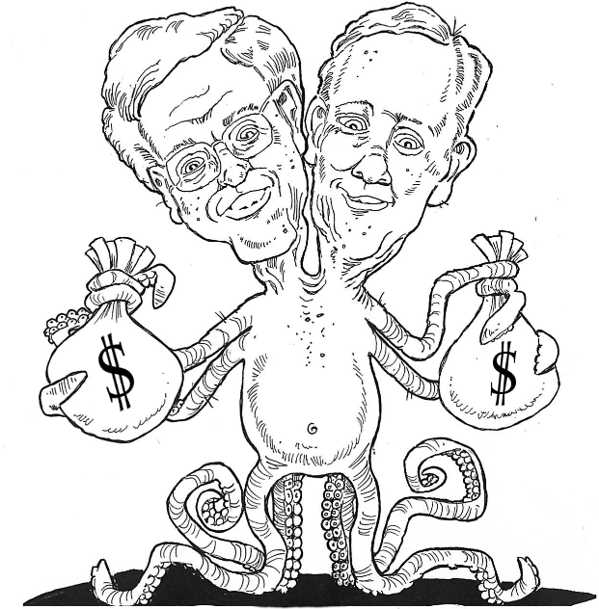

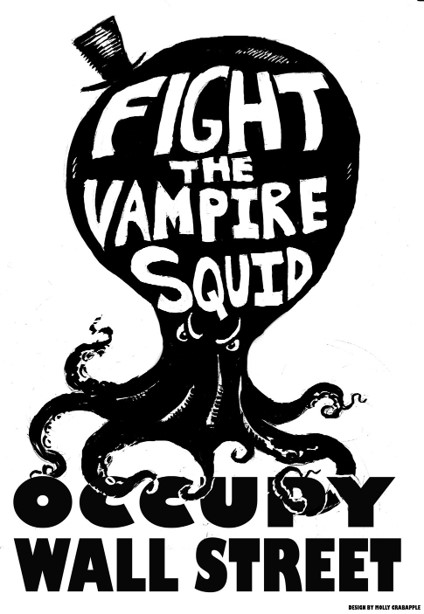

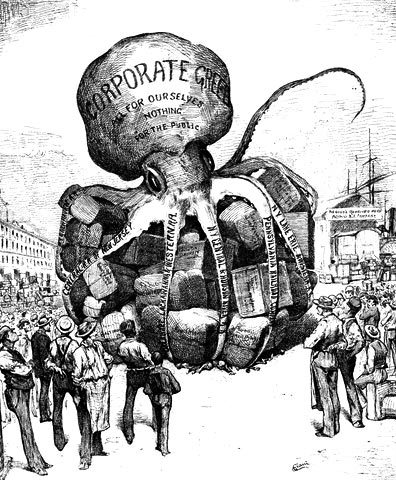

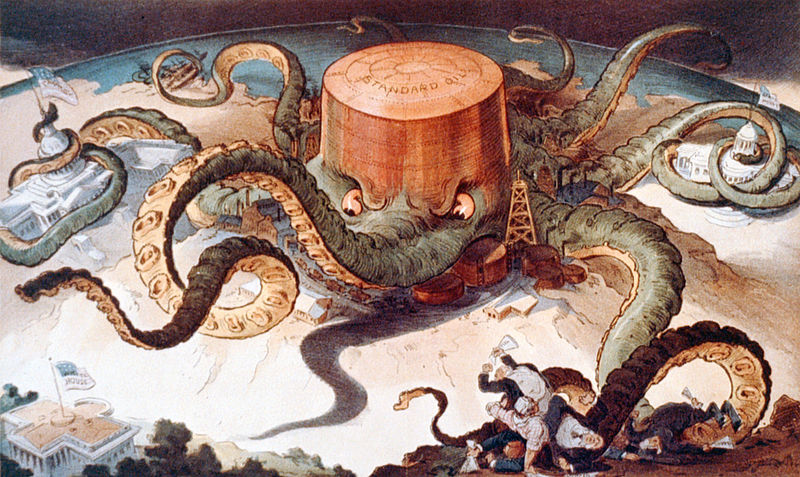

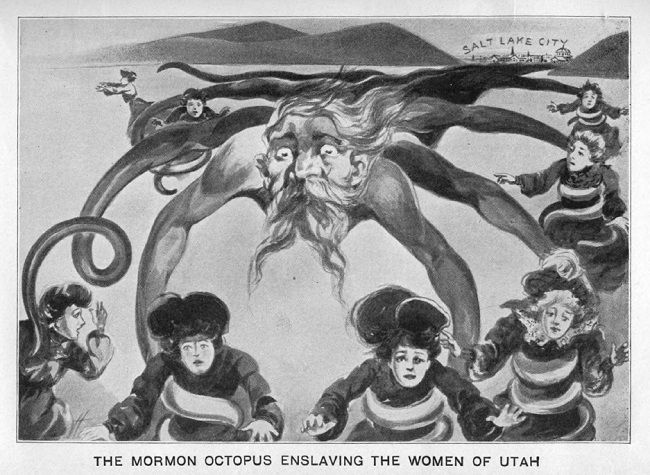

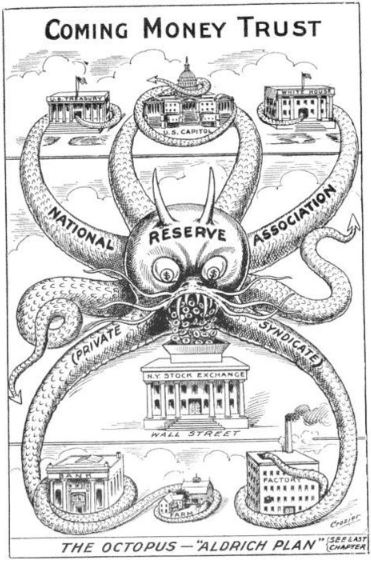

Melville and his generation did not know enough about great squids to develop their iconography. Even the scrupulous Jules Verne, whose sea-monster attacks the submarine Nautilus (tellingly, a mechanical pseudo-cephalopod) in 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, wavered in his explanation of his own creation between a giant squid and a giant octopus. The octopus eventually became an autonomous cultural trope symbolizing monopoly capitalism, imperialism, Communism, the Jewish global finance conspiracy, Wall Street, etc. The physique of the octopus — all head and tentacles, acquisitiveness incarnate – was perfect for the iconography of all-grasping and entangling states, corporations, and cabals.

As advances in 19th century marine biology drew more and more wondrous creatures into the rational science of oceanic ecology, squids and octopuses lost much of their status as threatening others. In the 20th century they were replaced by extraterrestrial aliens. Yet even in the transition to extraterrestrials cephalopodic traces remained. H.G. Wells imagined the Martians of the War of the Worlds as space octopuses,

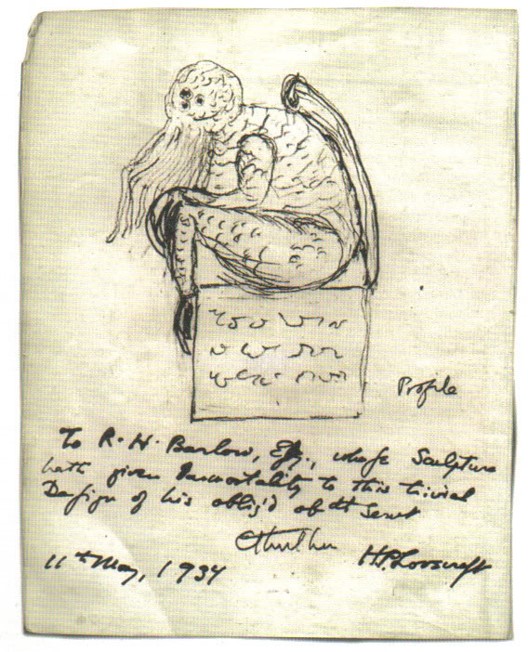

H.P. Lovecraft imagined the Old Gods of the Chthulu mythos as chimeras with squid- like heads,

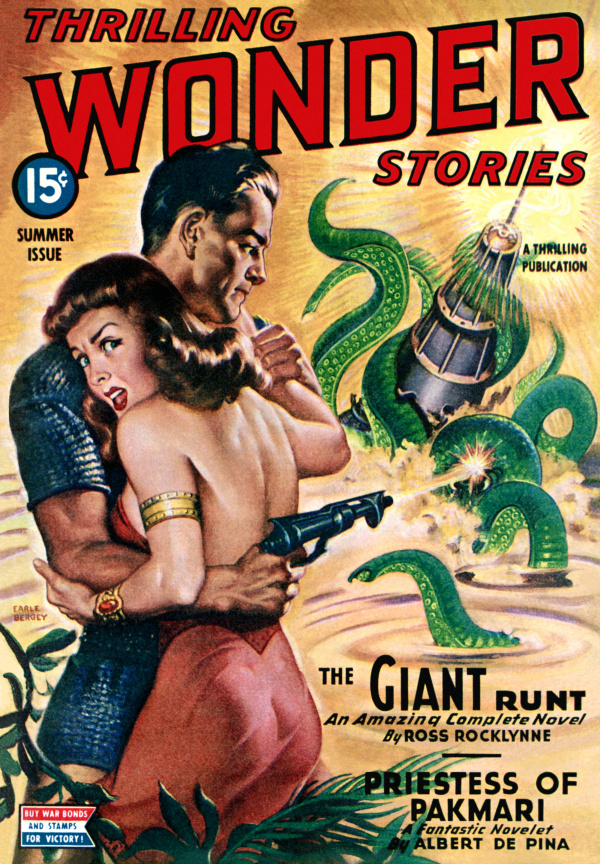

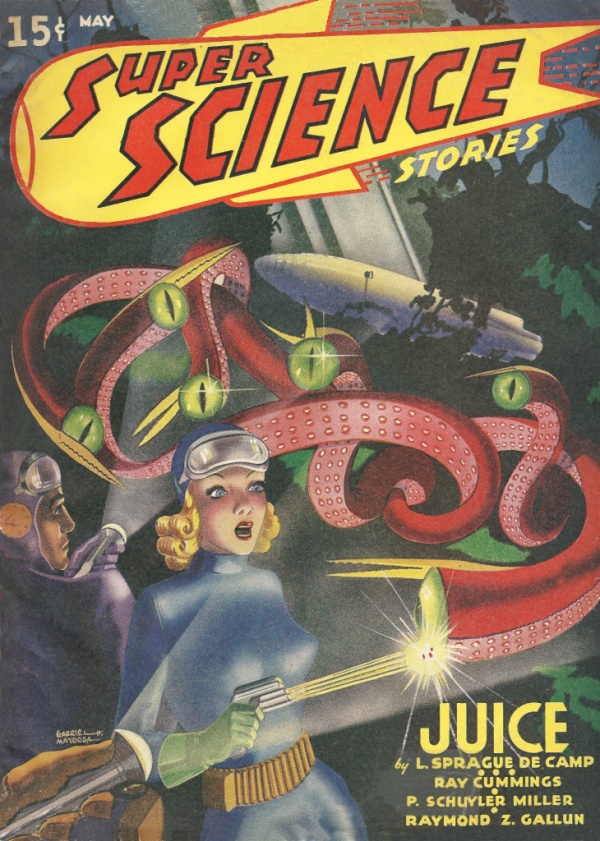

and cephalopodic aliens have remained a staple of pulp sf fiction and film.

Cephalopods have much to recommend them as contemporary scientific monsters. Their attacks occur on the boundary between enlightened technological civilization and the unconscious, unseen source of living matter. They are classical monsters, since their prodigious power and capacities, and their emergence from the depths, are signs of mind: their intention to engage with the human world, to bind it, and eat it … and to have sex with it. It’s a given in classical pulp fictions and iconography that all bestial others must be guided by the desire to sexually dominate human women – and we see tentacled monsters from the deep and outer space in many pulp sf stories and magazine art in the Golden Age of sf in the 1930s and 40s. This has now morphed into what can only be called the industry of tentacle sex. The Japanese art tradition has brought octopus sex into the open – and doing so has allowed us to focus on the specific combinations of sexuality and power that the cephalopod affords.

Parallel to their rise in the popular imagination, cephalopods have also become more interesting in scientific research. The ideal animal for biological research is one that is simultaneously alien and familiar. Its distance from the human guarantees that it will provide new information – about its nervous system, its adaptations, its range of behaviors, its ecological relationships, the quality of its sentience; but it must also be familiar enough to be recognizably analogous either to human beings specifically, or to other, better known creatures. Even in negative correlations there is a fundamental likeness that allows the comparison in the first place. And given that the modeling of likeness is distinctively an activity of mind, philosophical questions inevitably arise about whether the analogies are projections of human psychological interests, or whether the animals in question have similar, even if in some ways radically different, psyches. In other words, is sentience something that is similar in all sentient beings, or do morphologically different living things have radically different – and incomparable – minds?

Returning to “On Being an Octopus,” Godfrey-Smith argues that the differences between bats and human beings, however great they may be, are still much less than those between a highly-evolved mammal and a highly-evolved mollusc. While both mammals and cephalopods have intricate nervous systems co-ordinated by central brains sufficiently complex to provide problem-solving functions and learning, they are radically different both in structure and function. In Godfrey-Smith’s words, “The octopus, along with some of its cephalopod cousins, is an independent experiment in the evolution of a large nervous system, the only such experiment outside the vertebrate.” The Octopus is simply more of an alien than a bat – because of our divergence from common ancestor about 600 million years ago. Cephalopod eyes function similarly to human eyes – a model case of convergent evolution — , but a great deal of the octopus nervous system is distributed throughout the arms. One can posit that the arms may in some ways perceive the environment directly, in a form that blurs the distinction between feel and taste. (Furthermore, recent researches indicate the octopus skin has optical functions, as well.) Moreover, the octopus nervous system allows for significant autonomy of the arms from the brain, so much so that it is unclear to what extent the central brain can override the arms’ functions. It is possible that the arms have a certain agential autonomy. As more and more is known about octopus biology and behavior in the field, its differences stand out against the ground of the shared animal traits. Material questions give way to more subtle ones: what do these differences in perception, cognitive processing, and ecological entanglements mean for the way the octopus experiences the world? Put in terms familiar to animal phenomenology, what is the Umwelt of the octopus? What can it tell us about the human Umwelt? And finally, while we are entertaining these distinct biologies of mind, what is the character of our shared Mitwelt, the world we hold in common?

Biological research on cephalopods has entered a phase a de-alienation. Octopuses respond to experiments in problem-solving intelligence with surprising successes; and while observations in the field are still somewhat lacking, some researchers believe they show signs of observational learning and complex awareness of their environments. They are also undeniably curious. They are becoming increasingly interesting to us because they are seen to be increasingly like us: they have minds, individual personalities, and perhaps even a form of that Holy Grail of philosophy, self-awareness. Greater familiarity with the animals has stimulated more expansive modeling not only of cephalopods specifically, but of sentience and adaptation in general — not only of non-human Umwelts, but of the concept of Umwelt itself.

Nagel and Godfrey-Smith both speak of terrestrial creatures as alien but familiar. This is precisely the spirit of exobiology, the nascent field of modeling extraterrestrial organisms. Even if we believe that a true extraterrestrial alien may be unknowable, we still believe that if we know enough about its evolutionary ecological conditions we could understand it, even if only through back-propagation. If we know enough about the material universe, we can in theory know the other. And it would cease to be an other, at least epistemologically. So we have the same paradoxical situation in imagining both the alien and the truly different animal mind: identifying and describing the distinctively other, while asking questions and using categories emerging from human scientific salience. And we get characteristic phrases, like one octopologist referring to the octopus as an ‘evolutionary oxymoron’ – big-brained invertebrate. Octopus intelligence is observed, but it does not fit any of the categorical preconditions biologists have proposed for the evolution of intelligence. Among those generally accepted prerequisites are a large forebrain/neocortex relative to body size; a long developmental period before becoming independent from their parents; omnivorous extractive foraging; long life-span; life in complex social groups. Of these socio-ecological attributes, the octopus has almost none. (The exception is wide-ranging foraging, which some experts consider the deciding factor.) Nonetheless, octopus intelligence is observed, and increasingly. The placeholder concept to deal with this is the notion of “Convergent evolution.” This idea, while extremely important in modeling similar functions across species, is an entirely ex post facto concept – a fiction within evolutionary orthodoxy that shares some of the qualities of alien-human contact stories. Increasingly similar structures and functions are “discovered” in these most remote beings – similarities that (as yet) have no basis in physical kinship, only in modeling. Because octopuses seldom have fixed action patterns, they seem to have ‘mental images’ of appropriate homes before they dig, they find their way home using different paths that sometimes seem improvised, they recognize human persons and show preferences, they are ingenious problem-solvers, they sleep and possibly dream (they have color changes as they sleep), they exhibit motor play. Researchers increasingly use “shared development” stories to explain what physical evolution cannot. As one specialist imagines it:

Octopuses, naked and vulnerable, took to dens, as early humans took to caves. Like humans, they became versatile foragers, using a wide repertoire of killing techniques. To avoid exposure, they developed spatial sense and learned to cover their hunting grounds methodically and efficiently… In short, octopuses came to resemble us. Their hunting done, they huddle safely in their dens, a bit like early humans around campfires.

Meanwhile, the physical research refuses to yield similarity. In a recent article in Nature, entitled “The octopus genome and the evolution of cephalopod neural and morphological novelties,” published in August 2015, an international group of researchers reported that the genome of the California two-spot octopus had been completely mapped. The result, in the words of Clifton Ragsdale, a respected specialist, was the first sequenced genome “from something like an alien.” Surprisingly, the octopus genome turned out to be almost as large as a human’s and to contain a greater number of protein-coding genes — some 33,000, compared with fewer than 25,000 in Homo sapiens. Of the octopus’s half a billion neurons — six times the number in a mouse — two-thirds spill out from its head through its arms, without the involvement of long- range fibres such as those in vertebrate spinal cords.

Thus, a being that is viewed as simultaneously alien and also “convergent” with us, which we might phrase in science-fictional terms in this way: we make contact with alien others, and in the process of becoming familiar with them we establish more and more points of salience – the simultaneous radical difference and surprising likeness that characterizes dialectical thinking.

Which brings us to the Giant Vampire Squid from Hell.

In 1987, Czech-born philosopher Vilem Flusser, who spent much of his life in Brazil, teamed up with French surrealist graphic artist Louis Bec to publish a book in German that was translated into English in 2012 as Vampyroteuthis Infernalis. A Treatise, with a Report by the Institut Scientifique de Recherche Paranaturaliste. Written in the ostensibly objective language of a zoological case study, the treatise is actually a Borgesian fable – both a myth and philosophical fantasy. It describes an imaginary animal from the anima mundi – and stands as one of the most fully realized works of philosophical sf in our time.

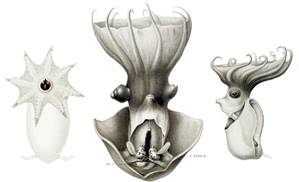

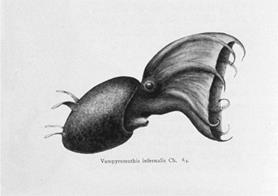

The biologists here know that there actually does exist a creature named the vampire squid from hell. It is a cephalopod, but not exactly a squid – it is considered a living fossil, the single member of the class vampyromorphida – and has enough traits shared by either by octopuses and squids to be considered a primordial cephalopod. It is about six inches in length, and inhabits the sunless, oxygen-minimum layer of the deep ocean. Not only is the vampire squid not a squid, it is even less a vampire. It is a detritivore, feeding on what is called “marine snow,” the detritus and excretions of organic matter that drift down from higher ocean levels. It acquired its name because of its dark, capelike mantle and ferocious appearance, but in this world it is a small, harmless sea-creature with almost as much in common with jellyfish as with real squids.

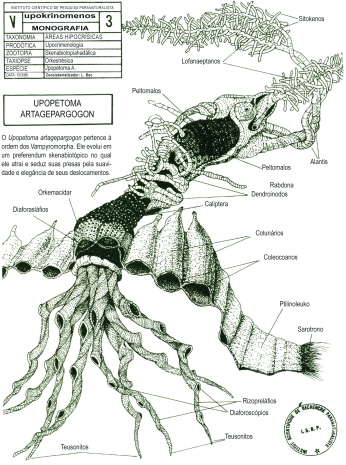

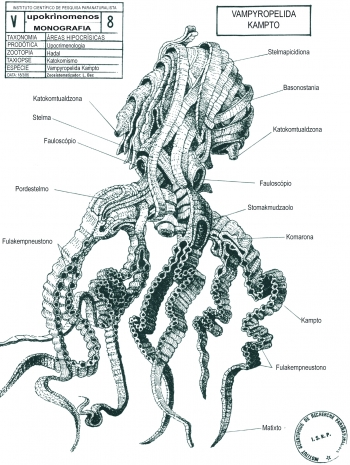

Flusser’s vampire squid from hell is not, however, from this world. It is a creature of fable – it has a strict purpose: to embody an imaginary model of the not-human – or more precisely, the anti-human. Although the precise dimensions of the Vampyroteuthis infernalis Giovanni – the name Flusser gives to his creature – is never given, we know from its purpose that it must be at least as large as a human being. In the same spirit, Bec draws and explains a number of vampyromorphs – inventing ruthlessly plausible new scientific terms to characterize imaginary morphologies and categories of behavior.

Flusser’s vampire squid is the direct inversion of homo sapiens. Flusser explicitly notes that the two beings share an evolutionary heritage going back to primordial worms – and so they are much closer to each other than extraterrestrial aliens would be. Indeed, as Flusser writes “we may share some deeply ingrained memories.” The treatise describes the dialectically opposed physical and cognitive evolution of the two species. The human leaves the rich ocean of primordial life toward the surface, the air, the sunlight. The vampire squid, by contrast, has moved downward, away from the sun, toward the depth of the abyss. The development of the two organisms in their opposing environments leads to opposite Umwelts. Human beings develop hands, far-seeing eyes, elevated brains, floating inner ears, ambulatory bipedalism, which lead to a three-dimensional sense of space, the division of time into past, present, and future, the faculties of rational abstraction. The vampire squid develops in the reverse direction, downward to the sea- bottom and darkness, perceiving with tentacles that are simultaneously sexual organs, creating its own bioluminescent light rather than processing the reflections of sunlight. We humans are active movers; vampire squids are passive receivers of their world. We try to co-ordinate diverse inputs through our eyes and neocortex; we are linear, as we walk. They are vertical, as is appropriate from their elongated spiral form. We view information in bits and pieces, and externalize our memories and impressions onto inanimate objects; they process all information as sexual impressions, and enlightenment for them is the synthesis of male and female internalized knowledge in orgasms that last for months. The inverse reflection extends to culture and politics – and indeed the expression of freedom that both creatures, each alienated in its own particular way, share. Humans seek to overcome their social-cultural divisions through an affirmation of love transcending division; vampire squids try to get free of their biological constraints – they, like most cephalopods, are born into egg-colonies of equal siblings. Freedom for this fraternity is in the form of hate, and its politics is cannibalism.

The Treatise is a virtuoso example of the “what it is to be like” thought-experiment, extended into a full-fledged thought-expedition. Flusser imagines an alternative evolution – not even an alternate one, but one like ours that produces something that we do not think the real one has: an animal that is radically different from us, yet similar enough to be our opposite. As Flusser writes, both are historical, both are alienated from their conditions, both are evolutionary dead ends. Flusser’s intention is clear, as he writes “we should gain a new perspective on our selves that, though distanced, is not transcendent,” by analyzing the human from the perspective of the vampire squid.

We have returned now to our original problem: how can we conceive of a truly alien mind without projecting our own categories onto it – the paradox of the alien is that it needs to be familiar enough to be recognized as an other. There can be no other, without a self; the reverse is also true. Inventing an other to reveal the self begins a process of infinite regression. In our scientific-materialist culture, many of us believe that if we study the others available to us – the near-abroad of animal life – we can put together enough data to be able to imagine an animal’s Umwelt. In science, we’d call it modeling. Many of us believe it is far more interesting to study real animals than to construct imaginary ones like vampyroteuthis infernalis giovanni, which inevitably bear the traits of the inventor’s time, place, and temperament. But at the end of the Treatise, Flusser remarks that biology has now reached the point where it does not need to find the fabulous giant vampire squid, but can generate it, along with all the evolutionary niches that are not filled. And at that point we may well ask how much of our human imaginations we have projected into the world, creating the other-minded animals and aliens that we lack in our enormous solitude.